Whit Pidot, MERU Strategic Partner

How The Travel Industry Navigated the Pandemic & What to Expect Moving Forward

Jason Armes of MERU recently sat down with Whit Pidot, one of MERU’s Hospitality Strategic Partners. Whit first became involved in the hospitality space in the 1980s, at age 14, when he convinced his parents to buy him a Sabre subscription and he started his own travel agency. Whit has spent the better part of the last three decades helping companies navigate complex issues in this space, as well as helped shape the hospitality practice and developed expertise while at McKinsey.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERU: Whit, thanks for taking the time to speak with us today. Obviously, we'll be talking about the impact of Covid, but first, to set the scene, can you talk a little about some of the larger challenges faced by these industries in the years leading up to the pandemic?

Whit: Sure, the largest issues that faced the airline and lodging industries are as follows:

- Capital intensity. These industries – at least for operators – are incredibly capital intensive. Especially on the airline side, the carriers need to be very careful about their fleet plans and how they outsource portions of their operations to express carriers. Those regional airlines provide capacity at a lower cost than the major airlines could achieve themselves, but it is not without tradeoffs. On the lodging side, there has been a massive move over the last 20 years to reduce the capital required by the major hotel players and move towards more of a franchise model.

- Labor costs. When company performance is good, labor often comes to the table asking for a bigger piece of the pie. That's not unreasonable, especially given some of the concessions that labor made over the years (like handing pension programs over to the government, leading to significant cuts for the employees). Employee relations are important and directly tie into the customer experience. They can’t be an afterthought.

- Focused target markets. Finally, another large challenge was strategically picking what customer types to cater to. You can't be all things to all people. So, you need to pick your favorite segments and figure out a plan to address those simultaneously; then, figure out how you can complement by picking up other segments on an opportunistic basis. Not many players can afford to fire customer segments (nor would I recommend it!).

MERU: In the early 2010s, there was a report published that showed that airlines were by far the most underperforming industry of all industries that touched the travel space. By the end of the decade, had the issues that drove this underperformance been resolved?

Whit: There was definitely progress going into the pandemic on some of these more significant issues. Right-sizing fleets and capacity helped, as did making labor agreements that corresponded to the value added by labor from the different divisions at different points in the business cycle. In the later 2010s the airlines captured a bigger share of so-called industry surplus.

MERU: Since the pandemic, what have been some of the larger challenges faced by the industries?

Whit: Really the largest concern was getting consumers comfortable with traveling again. It’s estimated that 2021 revenue was about 35% under what was expected in 2020 for the global travel and tourism industry, while fixed costs remained high. Attracting revenue-generating customers was imperative to the survival of players in these industries.

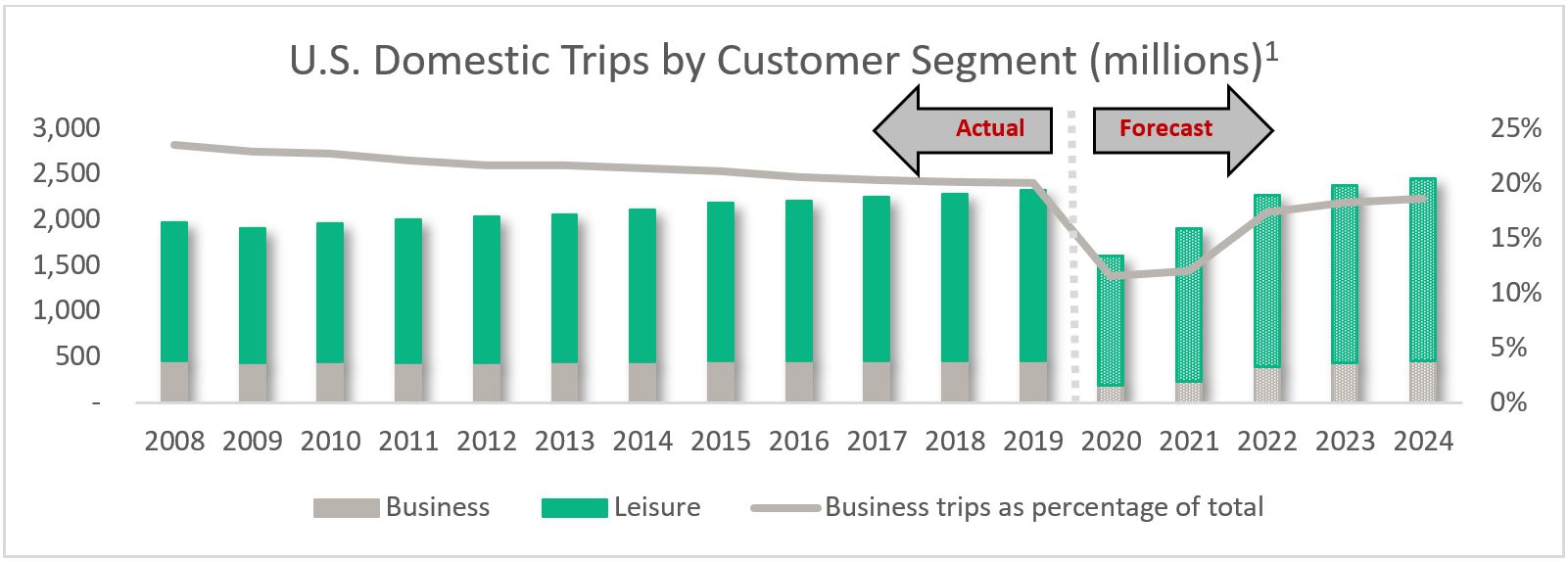

At the depths of the pandemic, business travel demand was down well over 85%. Remember, hotels in a relatively strong market would have had occupancy of about 70% before the pandemic. So, 85% down from 70% puts you in a really bad place. The airline industry had a similar narrative. Several players have made claims recently that they are down 'only 40%' at this point, which is dramatically better, but still leaves a lot of room for additional recovery. Interestingly, if you look just at average daily rates in the United States, independent of occupancy, there's been almost a full recovery in many markets. Occupancy often continues to be hammered, though, and in some cases down to 15-20%, especially during the week.

I used to tell my clients that travel demand forecasting was a mix of skills in history and math. Now one also needs a blend of science and psychology.

MERU: What were some ways that companies navigated issues created by the pandemic?

Whit: The best strategies have evolved as demand has (or has not) come back. Some major themes I saw across the industry included:

- Focused on regaining consumer confidence. Airlines were taking action to block middle seats and companies created partnerships with organizations like the Mayo Clinic and Lysol to display their dedication to cleanliness.

- Reduced services. Airlines and hotels alike got pretty good at managing costs in the midst of the pandemic, and often in the name of safety. For instance, suspension of certain in-flight services meant a significant reduction in free food and beverage that airlines had to “give” away. On the lodging side we observed reduced room cleaning and housekeeping, the closure of in-house restaurants / coffee shops, and the elimination of most club-floor amenities and lounges.

- Leveraged leisure demand. With business travel demand being so far down, the airlines would take what they could get on leisure to fill seats. They were agile in rebalancing their networks to put the capacity in places where leisure demand wanted it, like Hawaii. You started seeing a lot more wide-body service with international-configured airplanes going to domestic locations. On the lodging side, we are seeing a great deal of hotels starting to market towards in-town business travelers and “bleisure”. The former includes those who are not traveling for work in the traditional sense, but who want a place to escape the confines of their home and to work from a different location for a change of scenery. The bleisure travelers bring the family along and create dual-purpose trips.

- Adjusted booking / cancellation policies. One of the most significant changes was the general elimination of change fees. The exact structure of the change fees varied by company, but almost all of the major airlines abandoned the change fee ”forever”. Change fees made up a huge fraction of revenue, but with the uncertainly of the pandemic most customers simply wouldn’t tolerate them and so they wouldn’t even try to plan trips. Now, the migration to collecting fare differences for voluntary changes has turned out reasonably well. With the so-called penalty gone, many customers are more inclined to buy up to a slightly preferable itinerary when the stakes are more modest.

- Leveraged Loyalty Programs. To make it through times of low revenue, companies got creative to secure cash to keep up with high costs. Virtually all the major airlines mortgaged their loyalty programs in the last year to generate liquidity in case things continued to go wrong.

- Extended loyalty status. Most suppliers extended the loyalty status for virtually all members through 2021 and 2022. For the most part, the status rolls are now incredibly swelled and the competition among so called “top-tier” members for a scarce number of upgrades is getting tougher. We’re starting to see some dramatic shifts across suppliers in what customers will need to do to qualify for status in 2023.

MERU: As people who often traveled for work prior to the pandemic, Loyalty Programs are near and dear to our hearts. Now that status tiers are getting saturated, do you foresee reward points getting devalued?

Whit: I think the players are carving out different spaces for themselves in answering that question. This was definitely happening already pre-COVID, but during COVID as well -- there has cumulatively been major devaluation of many frequent traveler currencies. What used to be a domestic economy reward topping out at 50,000 miles may now cost you 200,000 miles. So, in terms of point inflation, it's sometimes massive. On the hotel side, it has recently become far more common to see partnerships with credit card companies, which is part of what's led to the point inflation on the lodging side as well. Credit cards offer massive point bonuses for signing up and the suppliers need to accommodate the redemption demand.

MERU: Of all the changes to loyalty programs and customer experience in the last few years, what changes will stick around, and are there more changes to come?

Whit: I wish I had a crystal ball for that, but here are my thoughts:

- Change fees. The airlines were unequivocal in their statements that change fees are gone forever. However, I feel like they will be making their return, just not in quite as explicit a form. For instance, one of the major carriers announced they're going back on the policy that “basic economy” tickets can't be changed at all, but they can instead be canceled with $100 charge and the residual will be available as future credit to use on the airline. Sounds to me like $100 change fee again.

- Alignment of Loyalty Program rewards with company incentives. Profit-based segmentation and targeting of customers will continue to remain prevalent in the airline and lodging spaces. One almost-immediate change under the auspices of safety was significantly reduced room cleaning and housekeeping. That conveniently was also a major cost reduction opportunity. Many of the players had already been experimenting with this before the pandemic, offering either loyalty points or some alternative perk in return for forgoing housekeeping on multi-night stays.

- Further shift towards leisure over business. I also think we will see companies balance their assets a bit more towards leisure and bleisure. Some say that business travel will be “permanently” depressed. It will be a matter of who makes the right bets at the right time, and how exposed one wants to be on the business/leisure fronts. Similar thinking in the context of physical footprint. Those with non-US exposure fared a lot worse in recovery as occupancies have stayed relatively low, at least relative to what has happened in the United States. Everywhere, business-focused hotels were hit a lot harder. The hotel chains and properties that were more focused on leisure – or amenable to leisure – fared somewhat better and recovered more quickly. Other hotels are trying to improve their leisure offerings to pick up some of that more rapidly recovering business.

- Highly specialized fare products. Going forward, I’d expect to see a proliferation of fare products. Companies are going to do as much as they can to distinguish their product offerings from those of their competitors, like being the “premier” luxury carrier, or being the lowest-frills, very cheapest offering. A similar theme will be seen in lodging. However, due to the massive numbers of brands in each hotel family, I’d expect to see more dual-branded properties, where the same building with common staff will have two brands of the hotel on the same property. Perhaps it will be on opposite sides of the parking lot, but sometimes literally sharing common walls.

MERU: What sort of disruption do you expect to see in these industries in the future?

Whit: Starting with airlines, there are always smaller, typically regional players popping up, trying to share in the wealth. As new competitors become less specialized over time, they can become much more of a relevant threat to the traditional business models. Several of these are springing up with relatively small-gauge aircrafts with relatively junior employees, since the companies were just created. Seniority or juniority of staff is a huge driver of costs for an airline business, so low costs today might not stick around. Some of the short-haul, small-gauge, next-generation air travel providers will provide air taxi type services, which will get you the last hundred miles home from a local hub. The technology isn’t there yet but it’s coming.

As for lodging, Airbnb is one immediate example that comes to mind that shook up the lodging space, and will continue to do so. Since its inception, we’ve seen plenty of look-alike players enter the market. Even some legacy hotel providers created functionalities to compete with Airbnb. I think everyone is being careful at this point not to bet the house on migration to that business model. Some hotel companies are probably more eager about making those divisions into massive businesses, or are opportunistically cannibalizing their own markets to take advantage of growth in the sharing economy.

MERU: Thanks so much for your time today, Whit.

To hear more interesting discussion around the travel industry, specifically travel hacks, check out the podcast below that features Whit.

1. Forecasted Number of Domestic Business and Leisure Trips in the United States, Statista

Authored by: Jason Armes, Principal