Wayne Thompson, MERU Strategic Partner

Evaluating the International Freight Market

Kathryn Dewing of MERU recently sat down with Wayne Thompson, one of MERU's Freight and Logistics Strategic Partners. Wayne is an expert in delivery logistics and has 25 years experience in advising companies on how to get product to customers more efficiently and cost effectively. He shared his thoughts on the current volatility in international freight markets.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERU: Wayne, thank you for taking the time today. Shipping costs to the West Coast have exploded. Can you give us a sense of why this has happened?

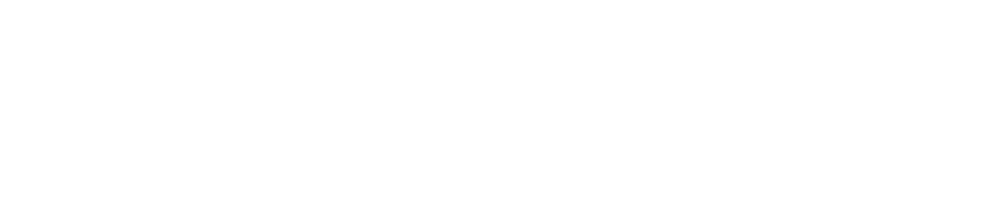

Wayne: Demand. Shipping carriers attribute price increases to increased demand for space on their vessels and containers. This increased demand was caused by a range of factors.

- Factory shutdowns in China. Just before Chinese New Year companies double down on their inventory to get enough product out before factories shutdown for two to six weeks. Due to COVID, factory shutdowns occurred pre-Chinese New Year 2020 and normal demand in the US and Europe was not met.

- COVID USA. Ports, manufacturing facilities and warehouses all shut down for at least the last 2 weeks of March 2020. This caused containers to start backing up at the ports.

- Demand switching. Increased discretionary income due to COVID restrictions reducing spending on items such as eating out and travel, as well as a stimulus package. This created huge demand for products that weren't forecasted to have demand such as furniture and home improvement products.

- Bad weather. Spending went up just in time for really bad weather in the United States. There was a two-week period in January where horrendous weather shut down the East/West train movement for a few days. In a normal year this can be absorbed but two weeks of the polar vortex and the issues that were happening in Texas created another issue in the supply chain that rippled back to the West Coast.

- Shortage of warehouse space. Warehouses were at reduced capacity. Companies were shipping out as much as they could to customers but the product in the warehouse was not what customers now wanted. Due to warehouse space constraints, the products that were in demand were sitting in containers. Containers were being held for longer as companies had nowhere to put their goods.

- Container shortage. There is now a container shortage in Asia. To ensure that they got access to containers, those companies that could afford to were paying more, causing prices to increase.

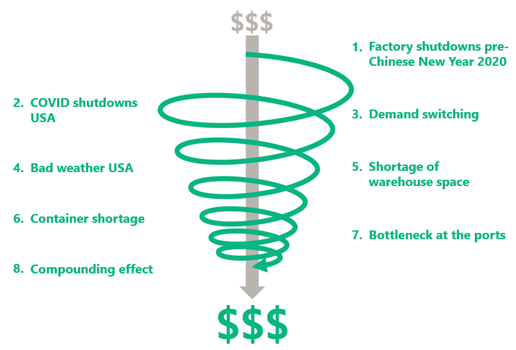

- Bottleneck at the ports. More containers were piling up but couldn't move inland. There was gridlock at the ports – “L.A. parking lot “– 90%of the vessels were not calling on time. Due to increased container turnaround times, you had less capacity coming out of China because the boats were sitting on the West Coast.

- Compounding. Companies continue to double down on their orders to try and fill a backlog of orders, meaning the problem never abates.

One result is that the ocean carriers produced record profits in 2020. Their costs didn't necessarily go up much but they were able to increase their prices simply because of supply and demand.

Ships waiting to dock at Los Angeles and Long Beach ports on Aug. 26.

Source: Copernicus Sentinel Data 2021 via Bloomberg.

MERU: Is the situation any better if you have contracted rates?

Wayne: There are contracts and pricing in place, but very few are holding those prices right now. Typically contracts are one year but that is always subject to a general rate increase (GRI) and a fuel surcharge that may or may not be defined. This could be $100, $400 or even $1000 or it could be $0. It is at the whim of the ocean carrier.

MERU: Any suggestions on how to reduce the freight costs into the West Coast?

Wayne: The container has become a commodity. Right how the priority for freight companies is how quickly you can turn around a container and send it back to Asia. The companies that can do this well have a better chance of getting containers at better rates.

There are a couple of other ways to reduce freight costs but they all require investment.

- Consolidation in China. This could be better packing in the container or reengineering of your product packaging to get more onto a container. For example, a bike company reduced the size of their boxes by 10% and went from getting 300 to 330 bikes onto a container. That doesn't sound like much but when you are shipping 5 million units a year, that's a significant cost reduction. Further, you are not wrestling for those extra containers with everybody else.

- Increase lead time. Everyone's trying to reduce lead time but those that have the benefit of being able to build lead time into their supply chain will get better prices. The slower you can ship it, the better off you can do. But that requires better demand planning, better forecasting with your factories and a real confidence in your inventory management to be able to stretch out that lead time.

- Use smaller vessels into secondary ports. Using smaller vessels into secondary ports like Everett, Washington or San Diego that don't necessarily have those deep berths is cheaper. Although that secret is out right now and everyone is trying it.

MERU: Have you seen any unique ideas from your clients in responding to this issue?

Wayne: I heard of one company leasing their own small vessel to bring their containers in from Asia and then selling the containers once they're done with them here in the US. They will actually make money on the containers. Not everybody can do this; you need a small, quick, nimble supply chain.

MERU: Has this had more of an impact on the West Coast than the East Coast?

Wayne: The East Coast has been less impacted as demand for volume is less than in the West Coast. Also, there is more warehouse space so companies are able to turn containers around a lot quicker and containers aren’t sitting in yards as much. This means that East Coast ships are able to stick to their schedules better than the ones on the West Coast.

MERU: What's the price differential been like?

Wayne: Pre-COVID it was $1500 more expensive to ship to the East Coast than the West Coast. This price spread has now inverted and it now costs $1500 more to ship to the West Coast than the East Coast.

MERU: What impact has this had on the demand for shipping to the East Coast?

Wayne: East Coast demand has increased substantially and now the Port of New York, New Jersey has eclipsed Long Beach to become the second biggest US port behind Los Angeles in terms of volume. Typically what happens is people will pivot to the East Coast and then once the congestion and pricing issues end they go back to the West Coast. We have seen East coast rates re-surge 15%-25% in the first few weeks of August and we have a premium on Panama canal moves as folks are shifting more to USEC.

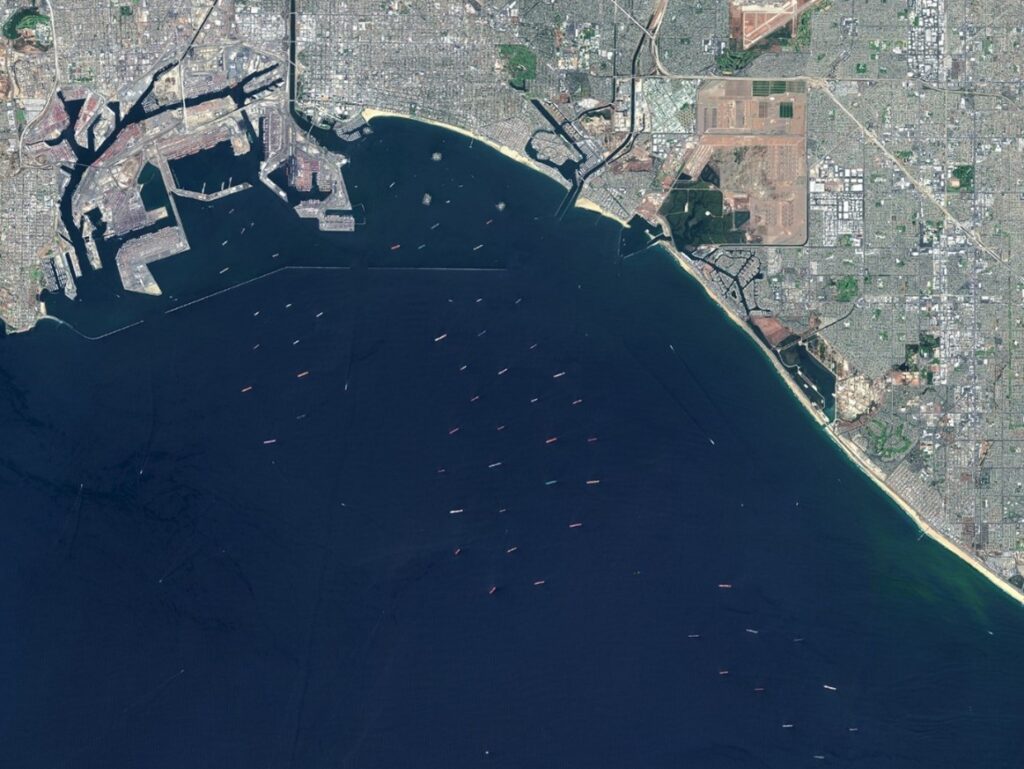

Average Global Price of a 40ft Container (across the seven major maritime lanes)

Source: Freightwaves.com

MERU: What considerations do your clients make when they flip back and forth between the two coasts?

Wayne: A lot of supply chains, if they have space on the East Coast or in the Midwest, will switch to the East Coast when the West Coast becomes busier. Therein lies the problem because if during the contract all of a sudden you want to start moving stuff to the East Coast, the carrier hasn't necessarily forecasted that. That could require bigger ships coming into the East Coast than they already scheduled. As contracts with carriers are very heavily influenced by the port pairings and forecast that you give them, if you change midstream you are looking at paying a premium.

MERU: What is your advice to clients regarding switching ports?

Wayne: We are telling our clients to take a longer-term risk mitigation strategy and continue to explore ways to get a percentage of their product in through the US East Coast, especially as problems in the US West Coast are happening more frequently.

MERU: What are the effects that you see as a result of these rising costs?

Wayne: Any major port in Asia to Southern California was priced at typically $1500 before COVID hit. We are now seeing those rates in excess of $7000. If these price pressures continue we are going to have to see some of these costs being passed on.

MERU: What other behaviors are your clients exhibiting based on these increased costs?

Wayne: Everyone, even some of the most sophisticated supply chains that we work with including Fortune 50 companies was in scramble mode. It was incredible to see the lack of risk mitigation programs.

I liken it to the Hunger Games - those that could afford the margin to secure containers in the beginning were doing it and those that couldn’t were left with late shipments. That seems to have settled down a little bit now just because everyone's in the same boat.

MERU: What other advice would you give customers?

Wayne: Smooth out your supply chain. Even in today's environment if shippers can count on you shipping 10 containers a week from Hong Kong to L.A. 52 weeks a year and turn those containers around quickly, they will favor you. You will save costs on shipping and you will save the nightmare of trying to figure out where your inventory is but you may incur costs on the North American end by holding more inventory. To me is it's less of a shipping question, it's what's your appetite to hold inventory here in the United States.

MERU: Some of that also must come down to warehouse optimization?

Wayne: Yes. The biggest mitigation to this current freight issue is having a big warehouse and being able to stuff it full of products. There is a cost associated with that but at least you have your product available for your customer and don’t have a stock out.

MERU: How do you think the current peak season will be impacted?

Wayne: The traditional peak season in ocean freight is September to Thanksgiving as companies are getting everything in for Christmas. What we're seeing this year is that it has been pushed up into June and July and that's likely to cause another backlog.

MERU: How long do you think elevated freight prices will last, and what do you see as the catalyst for change?

Wayne: Some people think that peak season will end at the end of Q3, others are not so optimistic and think that it will go straight through to Chinese New Year 2022.

MERU: What are the key indicators that prices are going to start going down?

Wayne: I would look at trending dwell times, meaning how long is the container being held up at various points in the supply chain? Right now these are at all time highs. A reduction in this means that containers are moving through the ports quicker. We would then need to assess whether this was due to new efficiencies or less containers coming through the port.

A second is forecasts compared to actuals for containers being loaded onto ships in Asia, because it takes them 2 to 3 weeks on the water to get here. If that starts to lighten up, that should start to push prices down but we won't know until bookings are down. It has to be a trend.

MERU: What impact do you think the Delta variant will have?

Wayne: If we do get more shutdowns then I'm worried. If they start reducing the amount of people that can go into the port complex and work, all bets are off. We're at full capacity right now and we can't handle it.

MERU: Do you think companies will have better risk mitigation plans going forward?

Wayne: If you'd asked me a year and a half ago, I'd say 90% of supply chains never learn and they just go into reaction mode but now I'd say 80% of them have learned and are applying lessons to their future plans. The reason I say that is when I would ask manufacturers what they were doing to figure out COVID I heard from a bunch of different people, “We’re dusting off our 2008/2009 playbook.” So whatever we learned during the Global Financial Crisis, we're looking to see what we can apply to the current situation. That gives me faith that people in the supply chain are actually learning from what they have been through over the last year and are probably a little more serious now about implementing those strategies going forward.