MERU Strategic Partner, Richard Peretz

The Future of Logistics with Richard Peretz

Nick Campbell and Kyle Sturgeon of MERU recently sat down with Richard Peretz, one of MERU's Strategic Partners. Richard is the former Chief Financial Officer of UPS.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERU: Supply chain has probably been more in the news recently than ever before, between the Los Angeles port situation and the Suez Canal. Are there any big picture lessons here, or are these just one-offs?

Richard: Actually, it’s the last year that supply chains have been in the news. If you look at the effects COVID had, and there's a structural shift in what's getting delivered to homes. Now, close to 20% of all retail sales are delivered to your home. On top of that, you've seen how important having a strong supply chain is to companies' success now.

You've had three or four years of growth in home deliveries from what you used to have in one year. For instance, groceries were not really a big category of home delivery in the United States but have picked up tremendously due to COVID.

MERU: It seems like the depth of the change caught a lot of folks off guard with not expecting things to stay at this level for this long. And that somewhat drove some of the issues, specifically on the West Coast ports.

Richard: I do think that in the last year you've seen a change that was much bigger than any of the past decade. It was driven also out of necessity, with COVID, but it was also once people started adapting there, they saw the convenience of it. And that convenience is something that's going to continue to grow.

You've seen the impact with all the carriers, whether it be the regionals, FedEx, or UPS, they've all picked up quite a bit of share in growth, 20 plus percent revenue growth and something like 60-70% of their packages are now going to homes.

MERU: For companies that are having to rely on these new supply chains, what should they be doing differently?

Richard: First of all, retailers have to understand that if they have a physical store there is a strategic advantage to that, because they are closer to the end consumer, so they can get something to their consumer faster.

The second is that they have to recognize that their system has to be flexible enough to know when the inventory is not in your local store, but it's close enough, across town, in a regional site, that it can be put into the system. And your systems are very important when it comes to that.

MERU: Are there other industries that you see increasing the need for more highly specialized logistics, like healthcare, where they will need to be more differentiated service?

Richard: Obviously healthcare is in the news due to the COVID vaccine. Having a temperature controlled environment, the systems that make sure that the temperature is staying where it needs to be, and being able to deliver with 99.99% efficiency to make sure that vaccine gets where it needs to be and not wasted.

Reverse logistics is another. If you think about the old traditional model, when you return something to the store, there was someone there that could look at it and decide if it goes back on the shelf, needs to go back to the manufacturer, or if it's so damaged it would be thrown away. Well, now in the online world, the same thing has to occur.

The other area is heavy goods. Remember when we started buying online, it used to be books. Today, you can buy patio furniture, you can buy furniture for your home. So white glove service is another big area of growth. And the customer expects the same experience no matter what size of the package is.

MERU: Amazon has made logistics into a competitive advantage. By having products so close to everyone's home that they can get it incredibly quickly, that has come to be the customers' expectation. They obviously have a huge amount of resources to be able to make that happen. Other retailers that aren't as well resourced, what are some ways they can compete with that?

Richard: The number one way is they have a physical store. It's a competitive advantage for that last mile. If you take some of these other companies, I'll throw out Target as an example. They have purchased two same day delivery companies so that they can participate in that last mile in a way that makes the most sense for them. But they also have the stores that are so close that it allows you to pick up a package without even going into the store. And I think those physical stores are a competitive advantage if you think of them as almost mini distribution centers.

MERU: For an online native retailer as opposed to someone who has that store network, is there a rule of thumb about what they would need in terms of either number of places in the country?

Richard: Generally speaking, between six and eight warehouses can get you within one or two days of your customer base, but it depends on where your customers live. if you kind of draw a circle 500-600 miles around a warehouse, that’s a good rule of thumb of what a warehouse can cover.

MERU: Richard, you mentioned the last mile is critically important. There are different ways that folks solve it in terms of just how to get it to the home. How does that evolve going forward?

Richard: There will be more players in the space. If you go back to last peak season Christmas time, you'd recognize that based on the amount of orders, that the market for home deliveries was larger by several million a day than what the capacity of the players in that space.

Obviously, you have the two big ones, FedEx and UPS, you have the post office. You have regional players that also play in this space and every part of the country has a different regional player.

And then you also have the Amazons, but you also have some grocery deliveries, you have autonomous vehicles that are starting to get into this space. But they're all going to help solve the demand, because demand keeps increasing.

Some of that demand will be met by the traditional players we're used to. Some of it will be met by autonomous vehicles, and then some of it will be new players that are emerging as well as the regionals.

MERU: Have you studied businesses like DoorDash and UberEats that are solving a similar last mile problem for the restaurant industry?

Richard: If you go back a few years, one of the major retailers in the US actually started to use these companies for its deliveries. The challenge for these businesses is they don't have the same economies of scale as the network players. So their stop density, the amount of miles between stops, makes it a little bit more expensive. Maybe as a result, they might have to play in higher end merchandise, where the value of the shipment is enough for the consumer to pay the premium to get it fast.

At the end of the day, there's going to have to be more home delivery capability. The market for it is increasing, and not all these categories make sense in a package environment. It makes no sense for example to put groceries inside a UPS or FedEx network.

MERU: Why is that?

Richard: UPS and FedEx are hub and spoke systems. A grocery store already has product near their customers. The cost to have the driver come in there and pick it up and make sure it's on the right route would take some economics out of the home delivery that the integrators have.

MERU: So the hub and spoke model just naturally doesn't mesh well with fulfilling an order from a local store to a home.

Richard: That's right. Also, the order doesn’t come in that far in advance. It doesn't give them a lot of planning time to run your network the most efficiently. If the grocer can fulfill out of the store, that may become efficient enough. They need to get enough density just at that store, so a driver can leave with seven, eight stops and they're go in a direction that makes sense chronologically, where the closest stop will be the last stop, the furthest away stop is the first stop, and they work their way back to the source.

MERU: It seems like the problem is even more extreme with restaurants. You don't have any flexibility in terms of time, and so it's just harder to put as many orders on one car.

Richard: That's right because you're also trying to maintain temperature and freshness. And that leads to a different kind of problem.

One of the ways that they're going to differentiate is with goods that have extremely high value. Where one to one touch makes the most sense, but that's not the biggest growth area of online deliveries right now.

MERU: I'm curious your thoughts as to how the USPS fits into the parcel delivery framework going forward. They've obviously been a major player to date. What does their role look like going forward?

Richard: Well, the interesting part with the post office is that while they're a competitor, they're also a vendor to all the big players, Amazon, UPS and FedEx. At the same time, you look at the economics and the cost USPS incur for delivery, we would expect package rates to increase. That being said, as long as the USPS continues to offer low rates, I think the three, I mentioned a moment ago, will continue to use them. But over time, I’d expect those rates to be adjusted to reflect their true costs and we may see a shift occur then.

MERU: Let's shift to the domestic trucking market. From the intelligence that we have, it seems like the market is incredibly tight. Is that the new normal?

Richard: It definitely goes through ups and downs. The way that carriers work in the freight market is they tend to buy purchased transportation from another provider. They don't necessarily own all the trailers and the tractors, so what happens is your purchased transportation goes up and down based on demand and capacity. And as demand, like now, is high, you pay more purchase transportation, but that purchase transportation is covered by contractual rates. So that’s what’s happening now.

MERU: What about other freight markets?

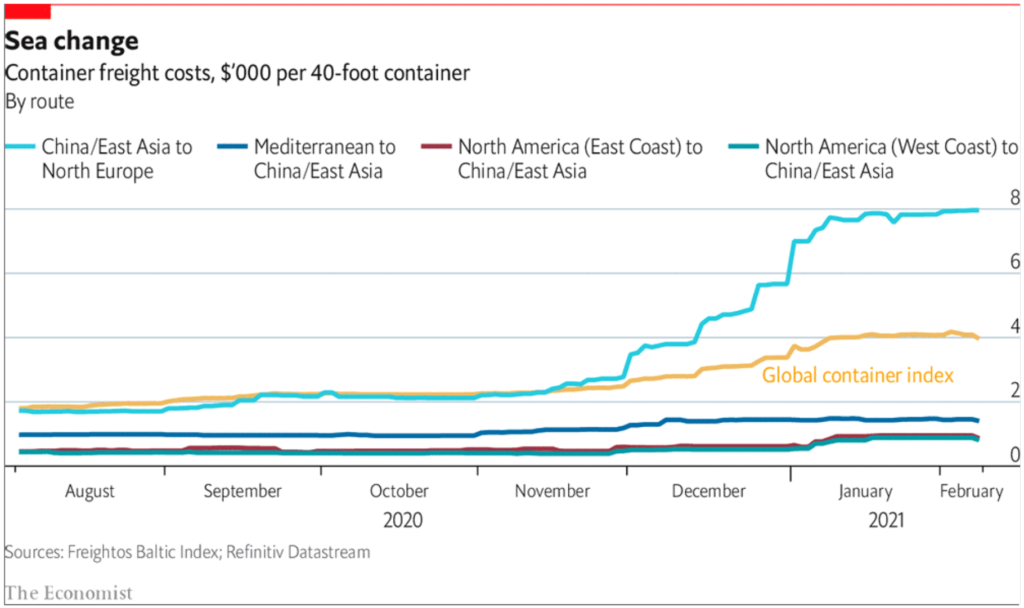

Richard: Truckload brokerage is asset-light, so this market doesn’t impact them much. Then you have the LTL market, which is more asset-intensive. The margins on those aren't as good. In fact, you've seen UPS just announce early this year that they were selling their LTL business. You have freight forwarders, which is both ocean and air. Because the number of passenger planes has come down, capacity got very tight on the air market. And then ocean freight, think what happened in the Suez Canal, what happens on the West Coast, anytime there's a labor strike there, or if there's big demand, that plays into the rates. So you almost have to think about each of these markets separately.

The perfect storm bringing them all together was the big change in demand from the pandemic. So when you see what's going on in the Suez Canal, it causes such a big disruption because things still need to get moved, and there’s less belly space in the air freight market.

MERU: What do you expect will happen with air freight? We saw those prices skyrocket last April and it seems like they haven't budged since.

Richard: I think the new normal is you won’t have anywhere near the capacity [belly space in passenger flights] you once had. So, when you think about last year, the general economy contracted. But as we grow, for example, if passenger flights are back at 50% of what they were, I don't think rates will be back to pre-COVID kind of capacity. We may see lower rates then the big COVID increase but higher that pre 2020 levels. It's all about balance - how much capacity is available (both belly and dedicated planes) and how much demand is needed in air freight for this recover. And prices will reflect that balance.

MERU: Has there been any competitive response, specific operators trying to soak up some of that demand?

Richard: Passenger carriers definitely try to soak it up, some carriers added freight only flights internationally during the pandemic. Dedicated air freight players added extra sections through the weekend to utilize the planes more efficiently. The question will be, what happens six months or nine months from now, when everything gets back to a new normal and what that means to people's buying habits? Most importantly, the players in air freight are used to staying flexible and making the necessary adjustments.

MERU: Revisiting a comment that you made earlier about autonomous vehicles, around solving for the last mile. How do you see those playing out in the near term?

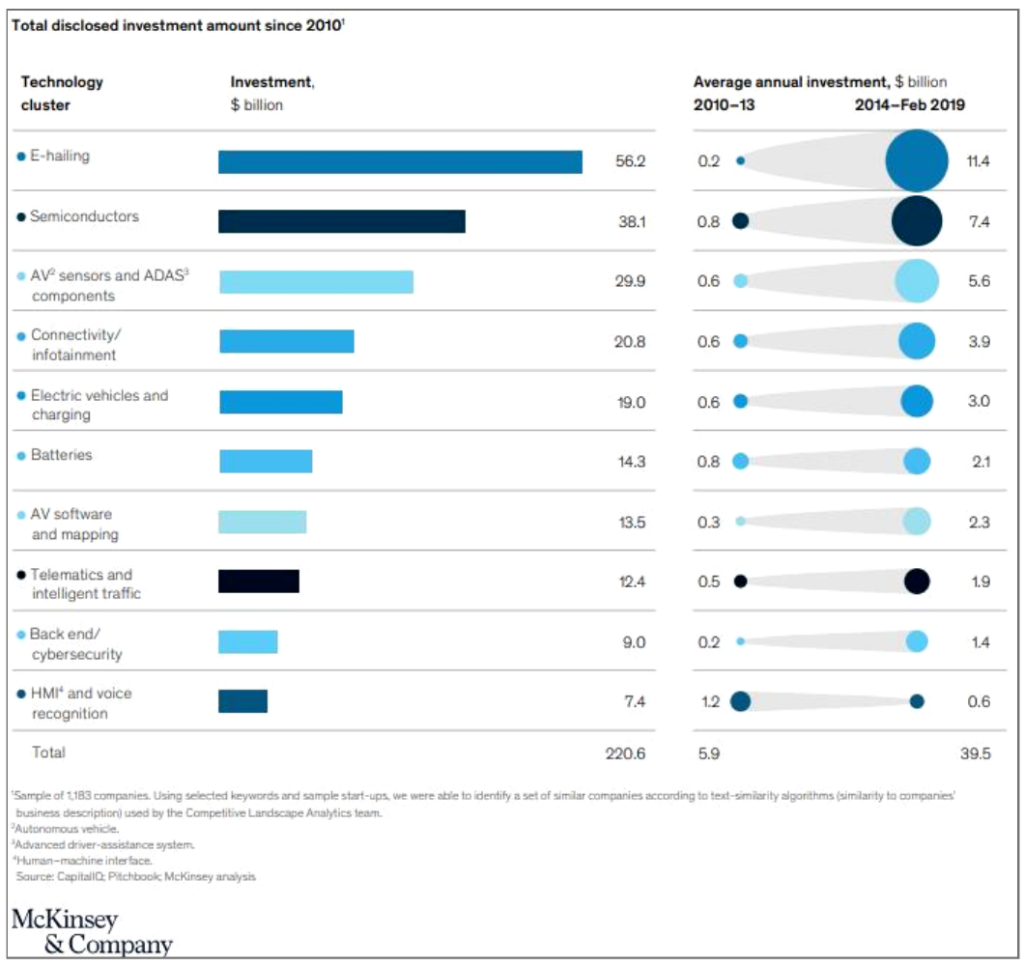

Richard: I think every one of those technologies, not just AVs but others, are important and will add value to the industry, long-term.

EV trucks are being tested right now, there are major manufacturers that are working with that. The real question is, will electric trucks be able to carry long distance, or will they primarily be used for in-city deliveries?

With autonomous vehicles, there are tests going on, but they're very isolated right now. AVs work best for long haul routes, not for the last mile. But regulations aren't all the way there.

The other big one is drones, which are already being used to deliver packages by UPS, Amazon, Google, FedEx. And they're occurring for routes that make the most sense because drones go over traffic. For example, when you have a healthcare type of delivery that needs to get to a destination on time, you can get it there.

At the end of the day, technology changes are going to have a direct impact on the industry. And they're going to make it more efficient and more competitive as well.

MERU: If you had to pick one of those technologies, what do you think we will see the soonest?

Richard: Electric vehicles are probably the one that's going to come out first, but they're probably not the most value added. Autonomous is obviously going to be very value added. And it's probably more long term -- when you get the whole environment to having autonomous technology, there will be less inefficiency than if you have one autonomous vehicle and 99 people driving, because the AVs talk to each other.

But I think all of these are going to play important roles in the next 5, 10 years. And I think they're going to be important not just for the delivery and supply chains, but for the economy in general.

MERU: It'll be fascinating to watch it play out. That's for sure.

Richard: Absolutely. With the large number of start-ups and venture firms working in the supply chain areas, the convergence of the physical customer needs with emerging technology will create more efficiency in the future.