MERU Strategic Partner, Taylor Holiday

Maximizing Marketing Efficiency and Deciphering IOS Privacy Change Impacts with Taylor Holiday

Kyle Sturgeon and Lucy Huang of MERU recently sat down with Taylor Holiday, one of MERU's Strategic Partners. Taylor is the founder of the digital marketing agency Common Thread Collective.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERU: Can you tell us about your background and how you came to start Common Thread Collective?

Taylor: I was a professional athlete and played baseball in the New York Yankees organization. When I was released from the Yankees, I had to go back and finish school because I had been drafted as a junior in college. At the time, I had a best friend who was starting a company, and he hired me for some part-time work. That company ended up going from a few of us in a tiny office to $60 M in revenue in 18 months. It was a wild ride.

So as that company started growing, I was put in charge of e-commerce and social media. Very quickly, I had to become the resident expert. I was managing a $5 M e-commerce business, half a million people on social, and brokering deals with Kobe Bryant in China, just stuff that I had no business doing as a 25 year-old kid. And so that was just a lot of happenstance and trust that people put into me based on community and network, and frankly privilege, that grew into a set of skills.

After a while, my friend Jordan Palmer and I joined forces to start what was essentially a consulting service to early stage consumer product sports brands, because that's the world we had come from. And then that grew into what is now CTC.

MERU: How do you differentiate your company from other digital marketing competitors?

Taylor: Our core value proposition is that we are operators first. One of the unique things about us is that we have the marketing agency and we also own and operate five of our own e-commerce businesses inside of a HoldCo called 4x400.

Because we’re coming from the side where we’re also building brands, it forces us to look at marketing from a financial-first position. We think a lot about our capacity to generate net profit outcomes for our business partners and work with them on forecasting and looking at metrics that inform merchandising and advertising strategies in ways that a lot of purely marketing-first agencies wouldn't.

MERU: How do you think owning the 4x400 business makes you see the world differently?

Taylor: I understand that the primary mechanism for growth is not improved efficiency in the ad account. You have to be able to identify all the available levers for increasing growth and profit. I’ll give you two examples:

Bambu Earth is our skincare business. It has an incredibly high retention rate for customers. We get about a 60% increase in customer value within 90 days of a purchase. But when we initially bought the brand, we were running at about a 1.2 ROAS (return on ad spend), barely breaking even on the first purchase. We were getting ready to shut down the business because we couldn’t figure out how to make it profitable on a 30 day P&L. But then we conducted this cohort-specific LTV (lifetime value) analysis and realized we were actually doing really well, just looking in the wrong time horizon. So just by understanding the financial construct of the business, we were able to 50X the company without ever changing any performance at the top of the funnel.

Another one of our businesses is a company called Slick Products. They sell wash kits to ATVs and dirt bikes. It runs efficient advertising [as measured by ROAS], but we couldn’t get it to profitability. The issue was that we have to ship bottles of soap all over the country, and so by switching to a bi-coastal 3PL, we were able to gain eight points of margin.

Many entrepreneurs we see think of the ad account as the primary solution to growth. And the reality is, oftentimes there’s an inverse relationship between spend and efficiency. If you’re going to maintain scale and growth, you’ve got to think about the other levers available to you. Candidly, most problems I see in earlier stage e-commerce businesses is a lack of financial sophistication.

MERU: It seems like you have a data-led approach to understanding growth. Can you explain your growth equation and how you use it to better engage with your customers?

Taylor: One of the primary things we think about is that there is not one templated solution for every business. So we came up with this premise of what we call the growth equation. Which originated as:

Revenue = Visitors x Conversion Rate x Average Order Value

We modified that equation by creating a financial metric we call cash multiplier or your 60-day LTV, which is the 60 day value of a customer. The equation becomes:

Source: Common Thread Collective Ecommerce Growth Strategy Blog

We focus on the 60 day LTV because most early stage e-commerce businesses from a cash position can’t flow into later value capture than that. So if you want to improve the contribution margin of your business, these along with variable costs are your levers.

MERU: Which of those four pieces tends to be the hardest to impact?

Taylor: I would say that variable cost is the hardest because people have the least clarity on it. They have accounting that lags 30, 60, 90 days to even get clarity on their costs. Additionally, adjusting or negotiating elements of it can feel overwhelming, and most people don’t have the visibility or know it well enough to make a change there.

Visitors tends to get a lot of focus because everyone can use more traffic. Conversion rate is complex because it’s hard to source out the causality of it. And LTV is more of a genetic attribute meaning it’s more related to what the product is. For example, the LTV of a $300 wallet isn’t going to be zero, it’s not intended to be purchased that way, versus if you’re selling a beverage.

In our experience, it’s easy to get more traffic. But how do you help your clients think about ways of getting “good traffic” – traffic that actually converts?

Taylor: So the initial macro categories that we’ll break it out into is organic traffic and paid traffic. What we want to see is a healthy diversification of traffic. A good benchmark is like 50-50 paid and organic as a framework.

Next, we’ll want to know where you’re under-serving the opportunity. Now, the opportunity is not the same for everybody. For example, organic search is a volume constrained channel. In other words, you don't necessarily control the volume of search related to your product category. You can have an influence on it over time, but volume is not be something a new entrant is going to alter a lot. So there's a two-by-two matrix where you think about volume and competition, and you determine the viability of that channel on the basis of a matrix and where you fall in that.

Same thing with email. How viable email is as a channel for your traffic and sourcing depends on how much LTV matters and how much revenue you’re going to drive off of your existing customer base versus net new customer acquisition.

On the paid side, the primary channel paid traffic is going to come from Facebook and Instagram as one thing, and then search in Google. There are also alternative channels like Snapchat, Pinterest, Bing, but those are generally much smaller. And we’d want to look at these and determine the opportunity relative to your present state in each of these channels and recommend a strategy accordingly. For most of these businesses, the primary mechanism of distribution is still Facebook and Instagram by at least 2X almost any other channel.

MERU: Does that normally stay the case when you guys get involved?

Taylor: Yeah. Because at this point, even amidst the chaos that we're living in on the iOS side right now, Facebook and Instagram are still a disproportionately more powerful acquisition engine than anything else. And everybody would love for that not to be the case, and they'd be in a lot less trouble if their media mix was diversified right now. But unfortunately, Facebook for so long has so outperformed every other mechanism of acquisition, that it was an opportunity cost to move any dollar out of that channel.

MERU: In other words, you're foregoing traffic and sales by putting your dollars elsewhere, even though it increases your risk by making such a big bet on one company?

Taylor: That's exactly right. And that was the trade-off that I think people made because they were running on such razor thin margins to begin with by pressing growth so hard that it wasn't actually viable to move the money somewhere else. The return rate on that other channel based on the construct of the business wasn't profitable. So it wasn't like they were choosing between multiple profitable channels of diversification. It was like, "We make money here, we don't make money here. How can we justify moving the dollars?" You can't.

MERU: Since you brought it up, what are you seeing with the changes to iOS?

Taylor: It's utter chaos. It's like suddenly, everything went dark and you’re thrust back into the days of TV and billboard advertising in terms of attempting to attribute outcomes. Because the primary issue at this point is not about whether Facebook generates sales. It's being able to assign that transaction back to the advertising in any viable way. The black box line that gets drawn by the privacy restriction, is that you can't map an online action to an in-app action. So basically, Facebook can't tell when a user clicks on an ad and then makes a purchase.

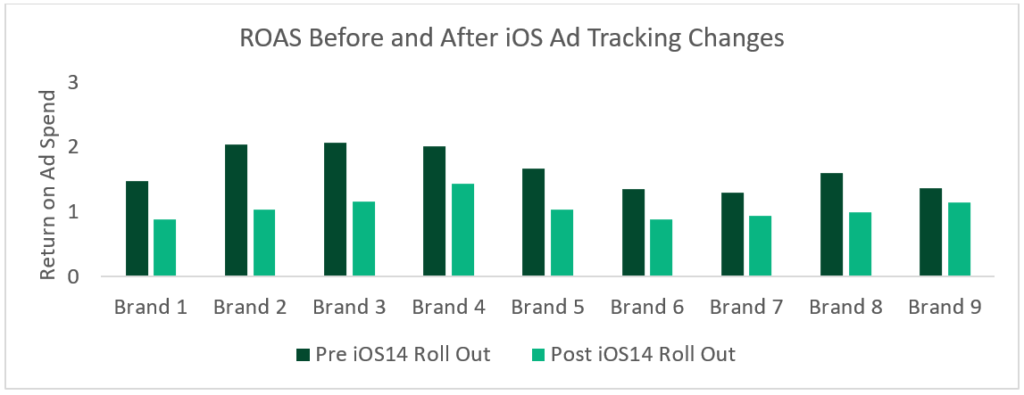

So like overnight, everybody's ROAS was reduced by 50%, just on a attributed basis. And everybody is asking, “How do I sort out the assignment of outcome in this black box?"

Well one, there's an immense amount of complexity in trying to now move from what was one primary data source to try and bring in multiple data sources to answer that question, which complicates reporting. Two, there's an educational element for customers where you now you have to move to a completely different set of metrics. Three, there's a level of genuine distrust that people have for both Facebook and an advertising agency saying, "I swear, there's purchases happening. You just can't see them."

And in light of that, the primary response that businesses have wanted to have is to pull back. And that is actually a move that many of them can't really afford to make. And so it creates a secondary order of problems, which is now the revenue starts to dip against a cost basis that they can't really move. So they're in this Catch-22 where they're unclear on how to spend, but they can't really afford to reduce the spend, and so it creates a lot of tension. It's been a lot the last few weeks.

Return on ad spend for several anonymized brands across beauty, fashion, and consumer sectors and how it has changed post iOS14.5

Source: Mi3

MERU: What are some of the things that you've been trying to do to help folks manage through it?

Taylor: We've worked hard to bring together a set of data to understand impact. You can use Google Analytics' last click attribution as a signal and try and understand the relationship between last click and historically reported Facebook ROAS. It’s not a perfect indicator, and oftentimes, the correlation between those things is actually quite small. It's one indication. The other thing we use is the quality of traffic metrics. So we can say, if their average time on site, their bounce rate, and their conversion rate on a last click basis are consistent or comparable to previous performance, we can hold ideas about directional performance.

And then on a macro basis, we use a metric called MER (marketing efficiency rating), which is just total sales divided by total ad spend. And then we'll even break down what we would call a weighted customer CAC, or total spend over new customer acquisition. And what we want to ensure is that on each given day, on the most macro level, is our advertising generating revenue at the efficacy that we need to maintain profitability? And then as we break that down, what signals can we use to make decisions on the individual campaign level about how to allocate that performance?

MERU: Do you think it gets to equilibrium at some point?

Taylor: I think what happens is that over time, Facebook's modeling of reported revenue just improves as the dataset increases, and as they work closely with other platforms on server-side integration. I think there's also going to be a big move to first party data where people are trying to collect some of this independent of Facebook. All of that will take some time to develop, and then you're going to have a clearer sense from people about the allocation of their media.

MERU: Let’s switch gears to branding. If you think about the biggest success stories out of the ones that you've worked with. Anything that you would say in terms of commonalities or things that stand out?

Taylor: Yeah, absolutely. There's a very common set of attributes amongst the winners. You either have to have awesome LTV, disproportionately acquisition returns, or really diverse traffic. One of those things has to be true, and the best brands have more than one of them. That is almost universally the case across the successful businesses I see.

Let’s take Slick Products, the wash kit, as an example. There’s a very strong relationship between the product and solution for a very specific group of people, which was great for LTV.

We also ran media for Theragun for a long time, and all we had to do was put up a picture of the product on Facebook and the returns were crazy. We had such disproportionate acquisition returns because of the novelty.

And we talked about a diverse set of traffic, which generally means they have one major organic channel. This can be an influencer with a large social following, some existing audience on like a YouTube channel, or some way that they access an audience and traffic organically. For example, we have a business that established a strong SEO position on an early term like CrossFit Sports Bra. As that space grew, it became a massive source of organic traffic over time.

MERU: And what are some trends you’re seeing in terms of the use of influencers?

Taylor: When you think about an influencer, they represent two potential assets. One is audience access. They have access to people, and then there’s just a question of the cost to access that group of people versus the cost of reaching a different audience. It’s becoming more expensive to reach audiences through influencers than elsewhere. Organic reach on platforms is also going down. So the value proposition of audience access has been decreasing.

The second thing influencers offer is content creation. And this is actually becoming much more the mechanism that brands are interested in using influencers for, which is to actually make content. And if you think about the modern influencer, a Tik Tok star or a YouTube star, they’re content creators. They built incredible content that was native to social platforms and built an audience based on that skill, such that their ability to create amazing content on behalf of your brand is really high. So brands are reaching out to micro level content creators and not paying them to post or reach their audience at all, but paying them to create assets that they then use in their own paid for media funnels.

The smartest influencers, the MrBeasts, the Logan Pauls, they understand that the way to maximize their value is to pull their audiences off of their platforms, and make sure they own direct access to email lists and SMS, which are much higher return rates for brands and can actually drive sales.

MERU: Thank you so much, Taylor.