MERU Education Strategic Partner, Carrie Stewart

Leading Public Schools Through the Pandemic

Kyle Sturgeon and Alissia Bell of MERU recently sat down with Carrie Stewart, one of MERU's Education Strategic Partners. Carrie has spent the last decade focusing on education finance and shared some of the challenges facing schools across the country, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

MERU: There's been a tremendous amount of disruption to schools across the country as a result of COVID-19. Where have you been spending the most time with your clients since the pandemic began?

Carrie Stewart: Great question. I want to step back for a second and talk about a few things regarding public education.

Public education in our country is a very local thing. It is a decentralized market with over $600 billion spent annually by 13,000 different school systems. Public schools are dependent on state and local economic conditions and tax-base wealth. There's little money spent by school systems that comes from the federal government in comparison to state and local funding. In many states, the school districts that have a wealthy local tax base are getting most of their money from there, through property taxes.

We're in a situation now where we know that state budgets are going to be hit hard. Our school system clients, for the most part, have not seen dramatic cuts yet. The problem is what is to come in the next few years.

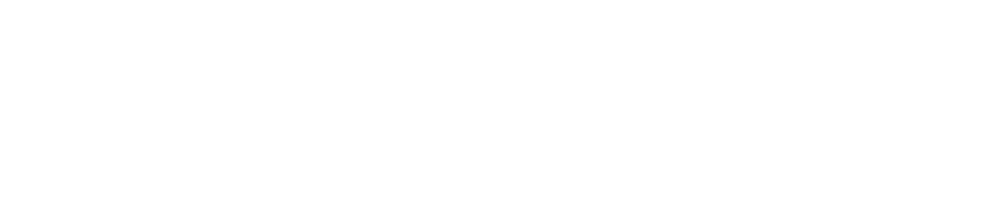

During COVID we have seen student needs increasing while funding is uncertain and likely to decline. This is a colossal instructional and financial challenge for school districts. Maintaining a balanced budget is especially difficult considering most school systems are contractually committed to staff salary increases no matter the funding outlook. If you want to address learning loss, you will likely want to offer more instructional time. But funding is in question, so how can more instructional time be afforded? The latest relief bill will help with some of that, but likely not all of it.

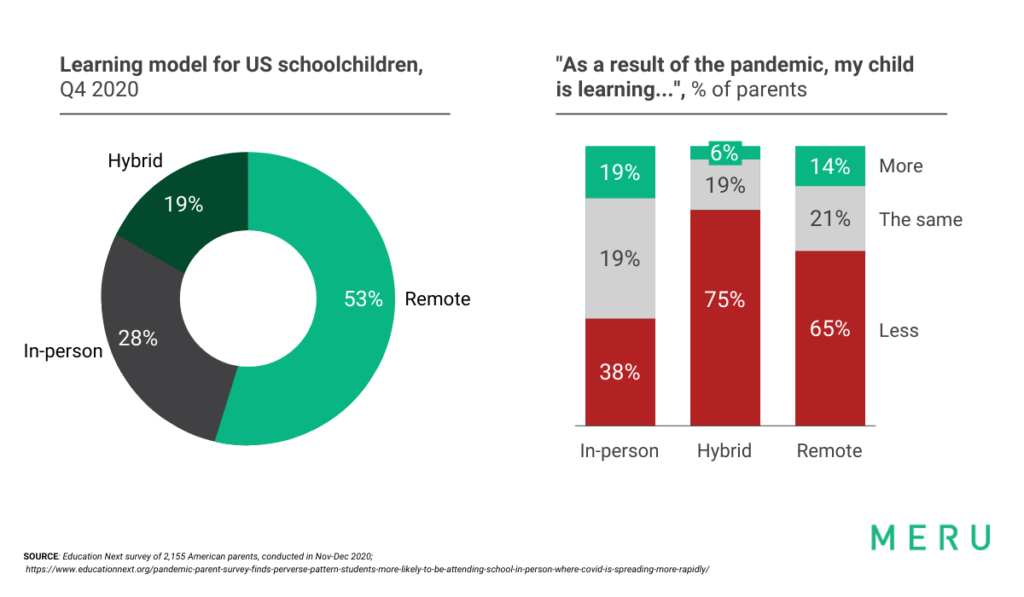

We had a pandemic before the pandemic, which is structural racism and an underfunding of public education, particularly for Black and Brown students. Now consider that when state budgets are hit, the impact from an education perspective affects more Black, Brown and low-income children – because school districts in lower wealth areas are more reliant on state rather than local funding. All of this presents challenges for our collective society over the next years.

There are some things that we are advising our school system clients right now, including the following:

- The time for aggressive planning for next year is now

- Use student data in the decision-making for setting goals and actions for learning loss recovery; leverage funding from the new relief bill accordingly

- Surface instructional plan & budgetary examples from other school systems to help think “out of the box” about how to approach next year’s instruction

- Set expectations publicly that funding, enrollment, and student needs will all be evolving – and plans will need to evolve in alignment

- Think about everything you're doing and the concept of the long term

Undertaking financial and operating planning within a multi-year perspective is really important. The other side of this is one I learned in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: this is a great disaster, and it is a great opportunity.

We have been experiencing a pause in normal course education. It is a traumatic pause where devastation has occurred. We must also acknowledge that things were not okay for many children in our country, prior to the pandemic. We now have an opportunity to reimagine what education should look like, and what funding should look like.

As ourselves: what is working now that we should bring back to the classroom next year? The old normal is not necessarily what is needed. Technology is here to stay. What else could be here to stay - should it be competency-based learning, multi-grade classrooms, small station rotation? Should some courses always remain virtual because it worked fine, and we could use the resources more effectively?

MERU: That’s really thoughtful. Maybe we can dive a bit deeper on the funding side. There's a big disparity between school districts because some have wealthier property tax bases and just happen to have structural advantages in terms of their funding. How much of a typical public school district's budget is local vs. state-funded vs. federal funded?

Carrie Stewart: It is very different state by state and city by city. I'm currently sitting in a city where over 95% of the funding comes from local. But right down the street, another school district has half of its money coming from the state. The district I am in has 100% of the funding it needs to provide adequate education. The one down the street, with a higher proportion of children in poverty, has 65% of the funding it needs to provide adequate education.

The economic shortfall I mentioned is really going to hit state budgets the hardest. That’s where we get back to the conversation on equity because it is the most underserved and lowest income areas that are most dependent upon state funding. In Fall 2020, the National Association of State Budget Officers put out guidance that state budget shortfalls are just going to continue to grow. That is devastating, especially when you recall that school system cost structures are not as variable as one might think.

MERU: What about overhead? We have read a lot on the post-secondary side about how the number of administrators has grown so much faster than the number of professors, which contributes to the rising cost of college. Have there been similar trends in public primary and secondary education?

Carrie Stewart: Yes and no. You definitely hear that from some stakeholders. That said, we've worked in some of the larger urban school systems that have labor contracts that require certain levels and types of staffing positions as well as salary scales. So when revenues dropped, particularly during the Great Recession, they had little other places to reduce spending other than the central office. You can argue that certain school districts are so under resourced from an administrative perspective that it's dysfunctional. And I think that that's hard for folks to believe, but we have seen the data to actually know it’s true. It takes a lot of resource both inside classrooms and outside classrooms to provide exemplary public education.

MERU: What are the consequences in the classroom from that type of under resourcing?

Carrie Stewart: Well, you need a strong central planning function to set school performance expectations and a vision and standard for educational success. You need a central service function to think strategically about how money goes out to schools, especially in large school systems where you have dozens or hundreds of schools serving all kinds of different neighborhoods, meaning the student need at one school is completely different than the other school.

You need planning to determine what strategies and resources need to be allocated in order to best serve students in such a diverse kind of population. If you don't have that, you can't expect to see the outcomes that you'd want.

And the central planning function also has a critical role in understanding community level needs and how the school building footprint across a city should align to those needs. In communities across the country, there are school buildings that are 50 to 100 years old in need of significant investment, but people do not live in the same places as they were 50 or 100 years ago, so you need a central function to determine where we need to invest as a school community.

Overall, it’s a coordinated effort to decide where and how to invest to best serve families.

MERU: That also calls to mind the idea of consolidation especially if, a school was originally designed 70 years ago and populations have shifted. Are there “extra schools” that you could consolidate so at least we are investing the scarce dollars into fewer buildings?

Carrie Stewart: From a pure business standpoint, perhaps school consolidation looks like a real opportunity. But from a community perspective, it’s a completely different thing. How do we expect communities to recover, to rise up if we don't invest in them with a school?

MERU: How do you see charter schools playing to this?

Carrie Stewart: About 6% of public school students in the United States attend public charter schools. Charter schools are predominantly operating in underfunded school systems and serving children from families historically underserved. They're private entities, often non-profit, receiving public dollars. They have an added dynamic compared to school districts in that they are often smaller and younger than school districts with less access to capital markets and thus they have to be more focused on liquidity on a month to month basis. The typical charter schools we work with have 40 to 90 days of cash on hand.

In addition, they have multi-year charter contracts to operate their schools, often between 3-10 years, which means that the ability to finance a new building or get an operating loan is a higher risk profile. Most charter schools have been able to access the recent federal relief funding and small business association financings. By and large, just like public school districts, charter schools are doing their part to try to provide innovative solutions for underserved children across our nation and will be significantly challenged during the economic crisis.

MERU: What gives you the most hope in terms of the direction of our school districts despite the monstrous challenges that they face?

Carrie Stewart: Sometimes when there is tragedy, our eyes are more open to what is in front of us. I do believe that people are seeing more of what was already in front of us now during COVID-19, particularly in early childhood with the lack of childcare and realizing how dependent our economy is on that. I hope our society will begin to realize where investment needs to occur. I hope our society will see the need to invest in historically underserved communities, particularly people of color. We now have a once in a generation opportunity to reimagine what things can look like for all children. Will our state and local leaders take this opportunity? I hope so.

MERU: Thank you so much Carrie. Your passion for this work really comes through, and it's incredible. We appreciate the opportunity to speak with you.